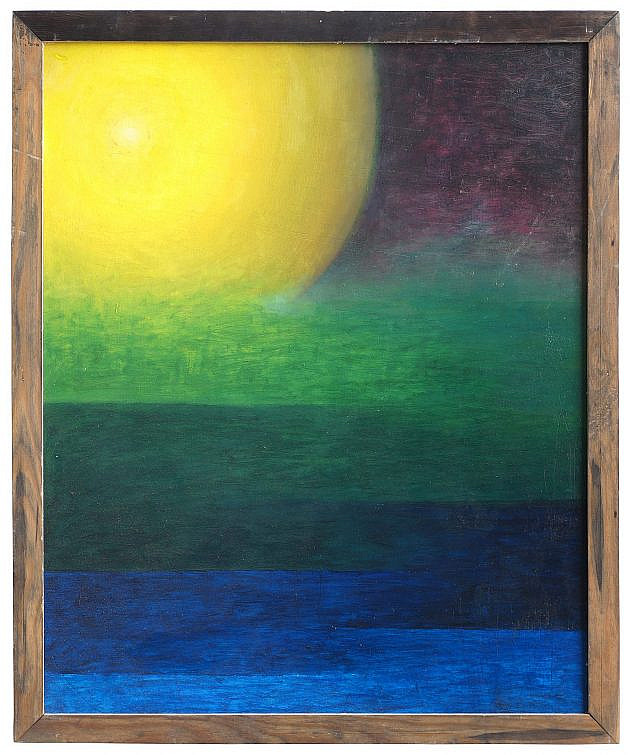

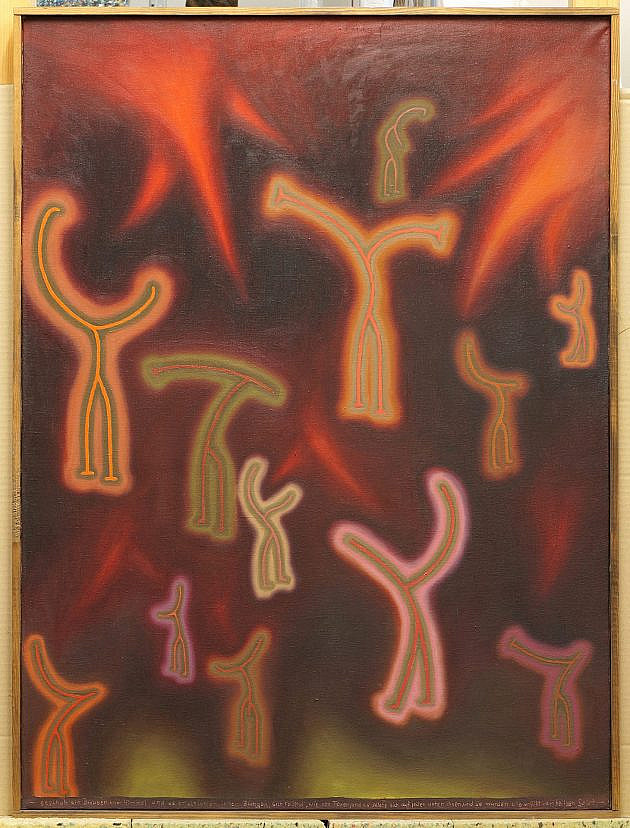

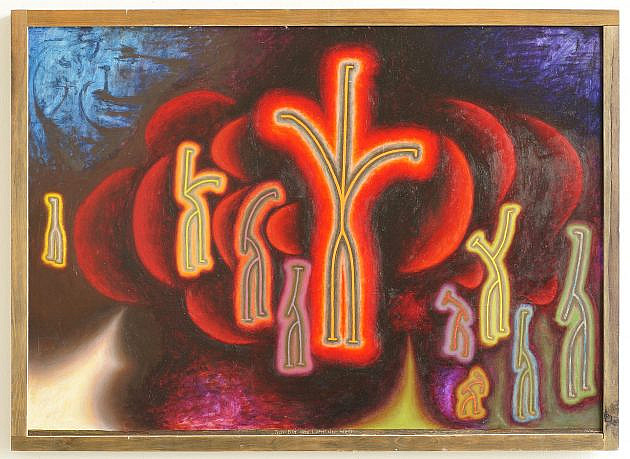

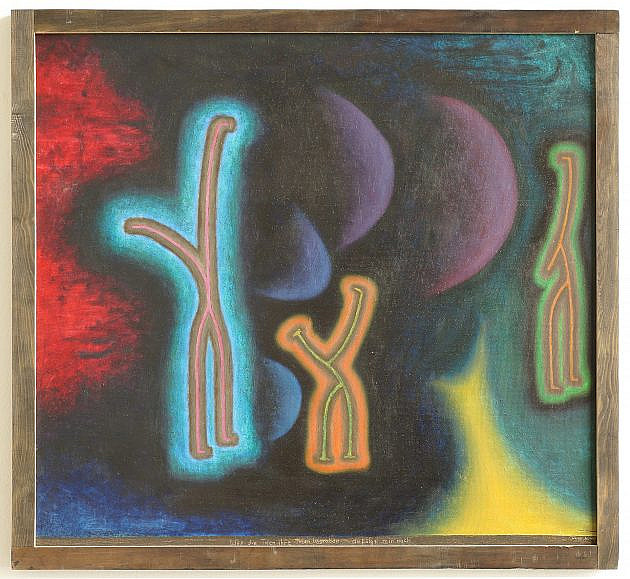

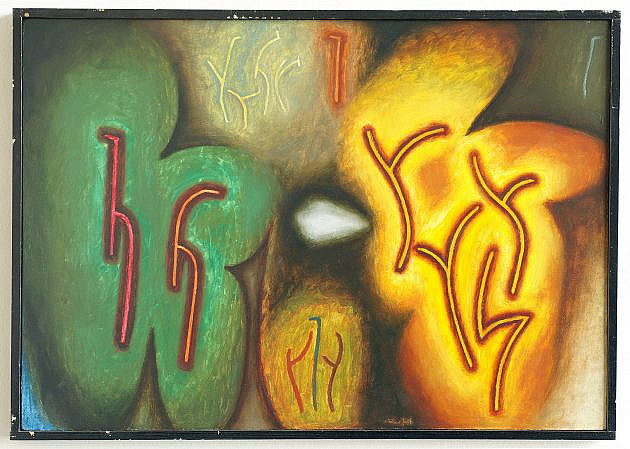

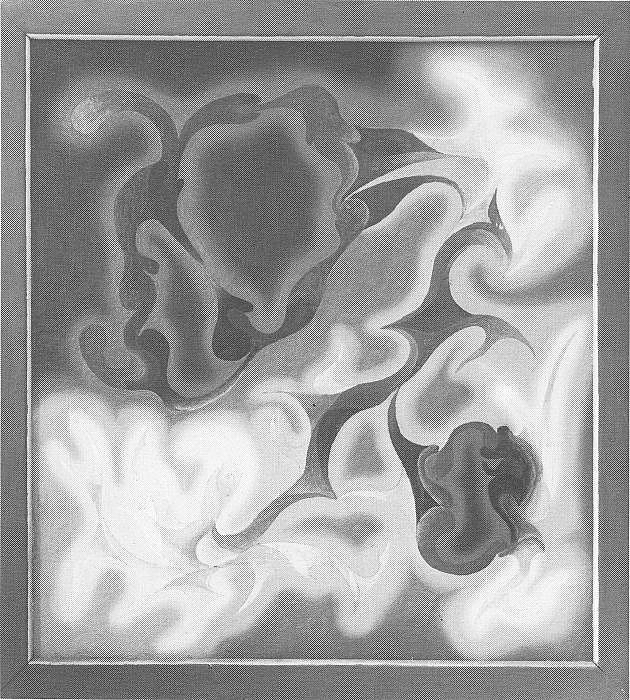

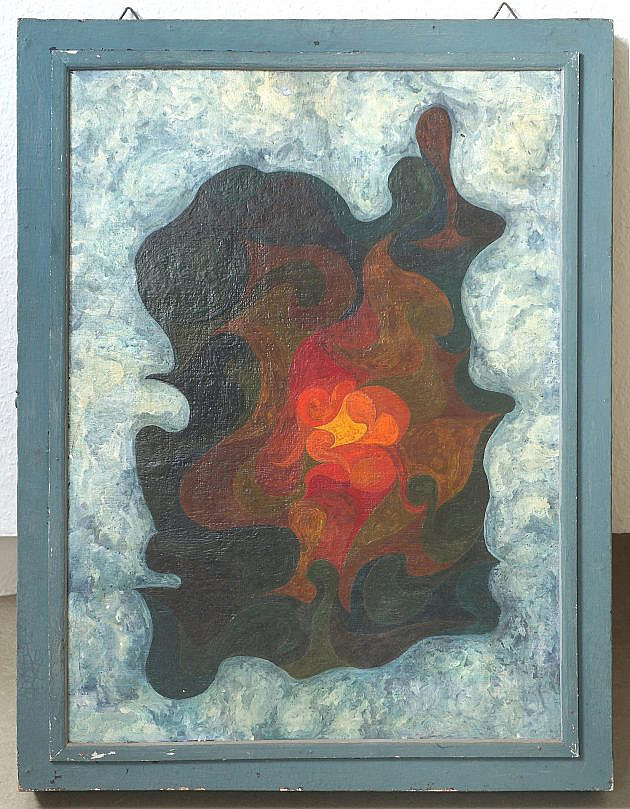

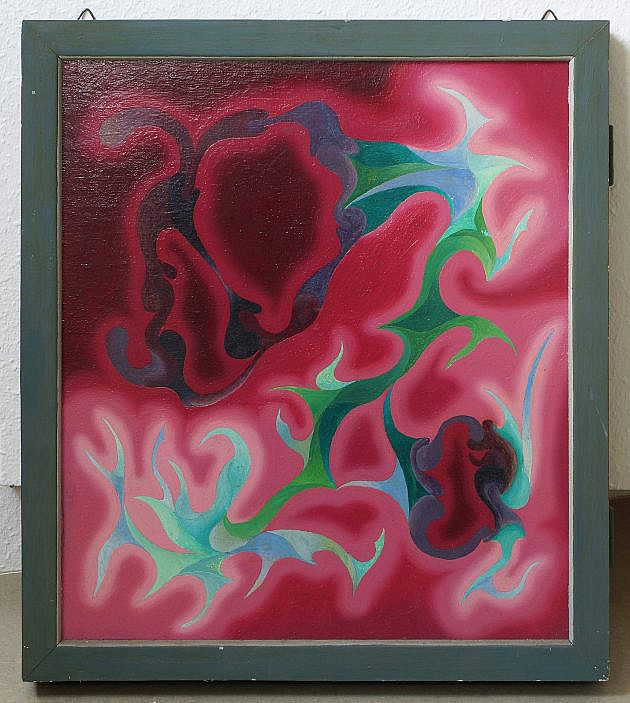

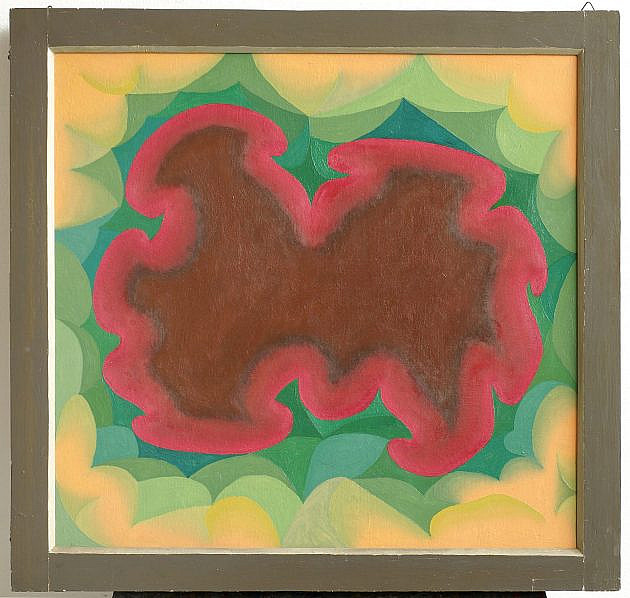

Frühwerk / Early work

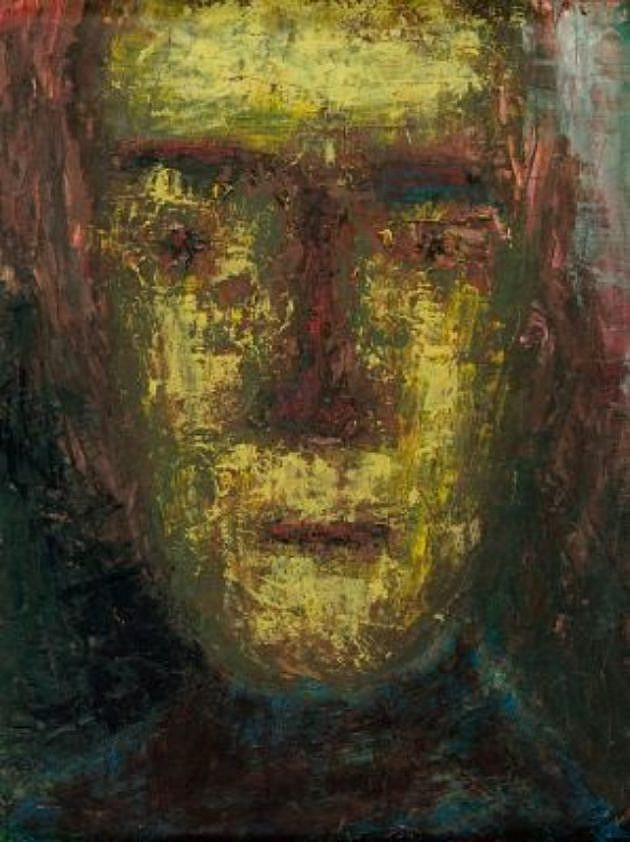

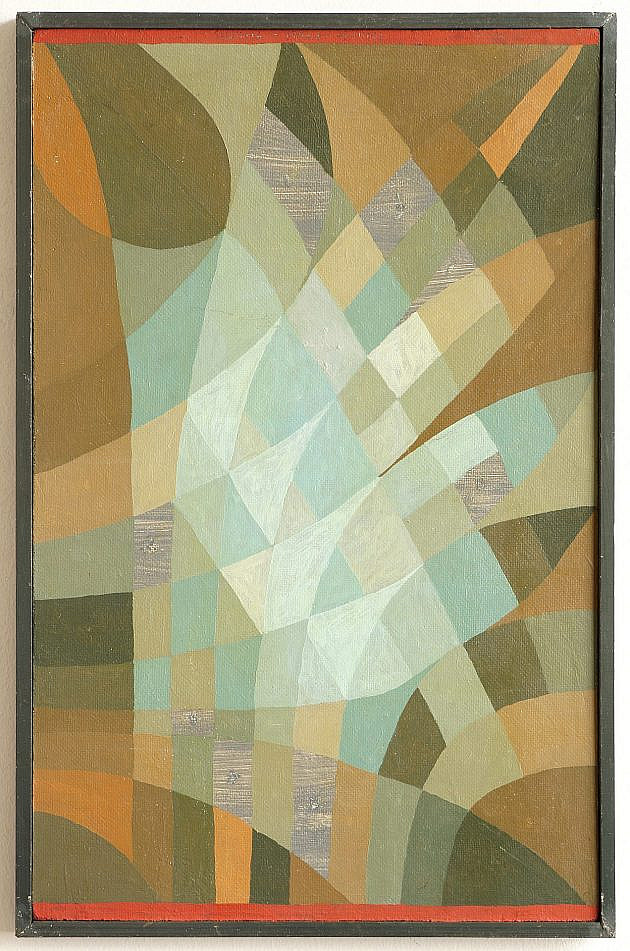

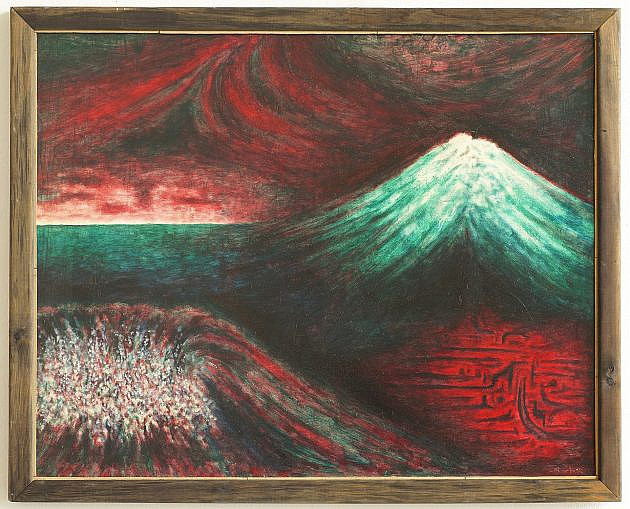

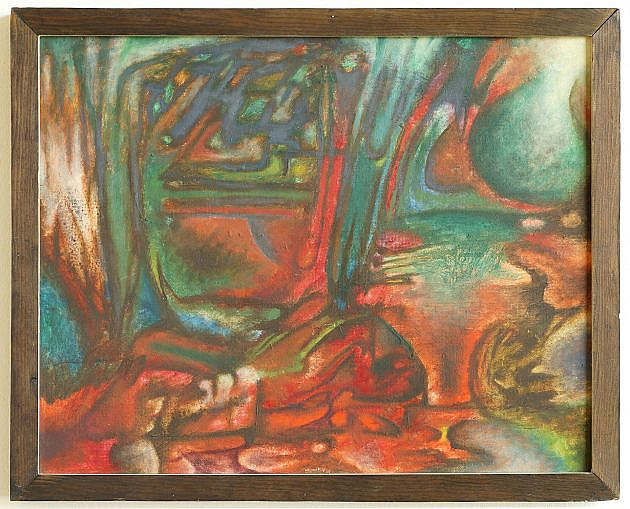

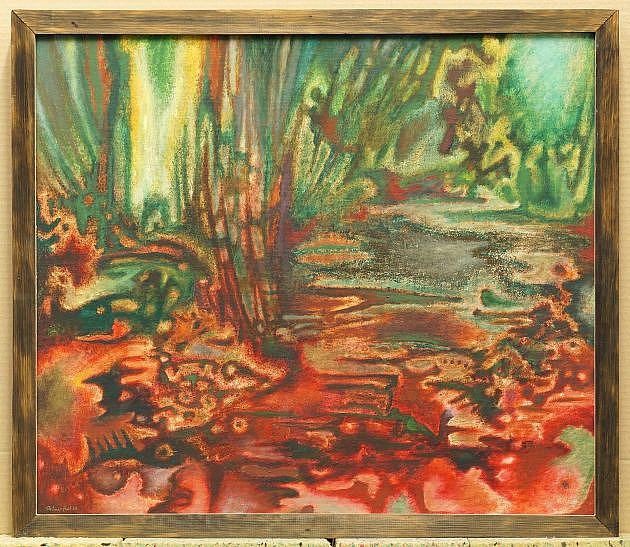

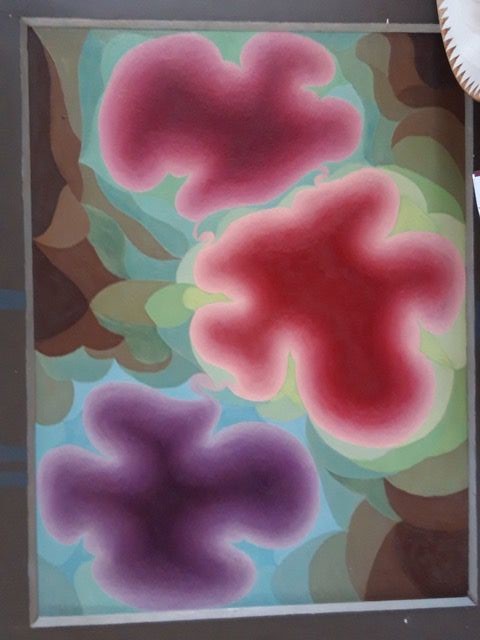

Die ersten Bilder, mit denen Reimer Jochims (damals schrieb sich der Künstler noch mit „ei“ statt heute mit „ai“, d. Red.) zu seiner eigenen künstlerischen Sprache findet, tragen die Spuren einer doppelten Auseinandersetzung. Sie verarbeiten nicht nur Elemente aus der Malerei der Nachkriegszeit, sondern sind in gleichem Maße durch eine intensive Realitätsbeziehung geprägt.

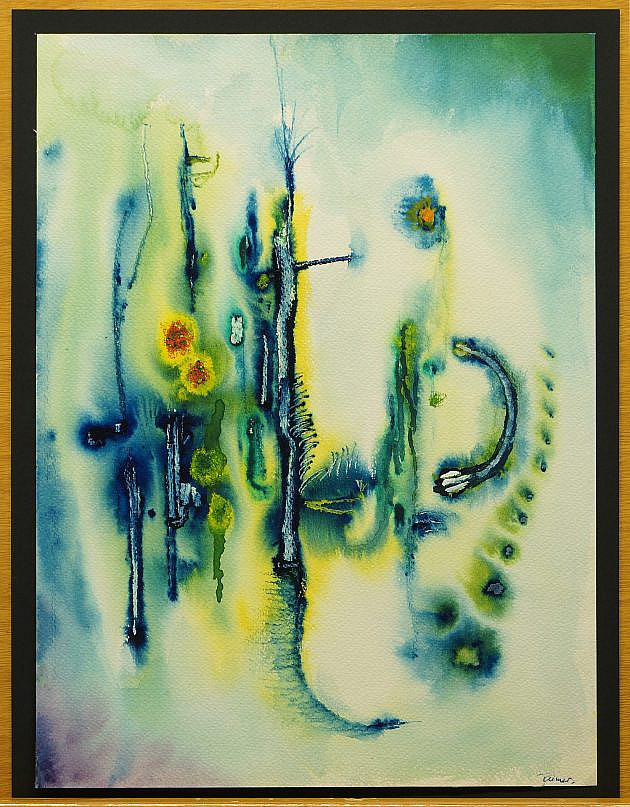

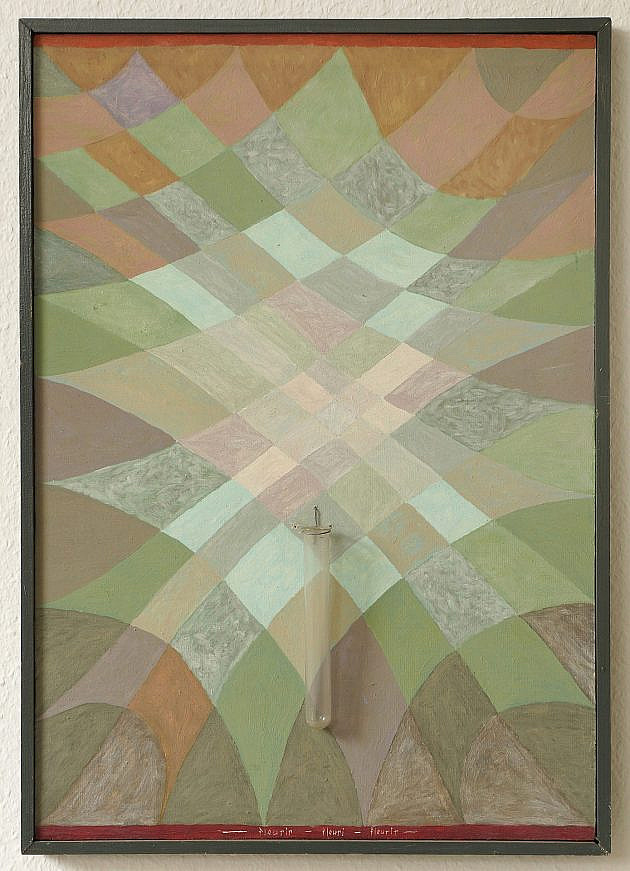

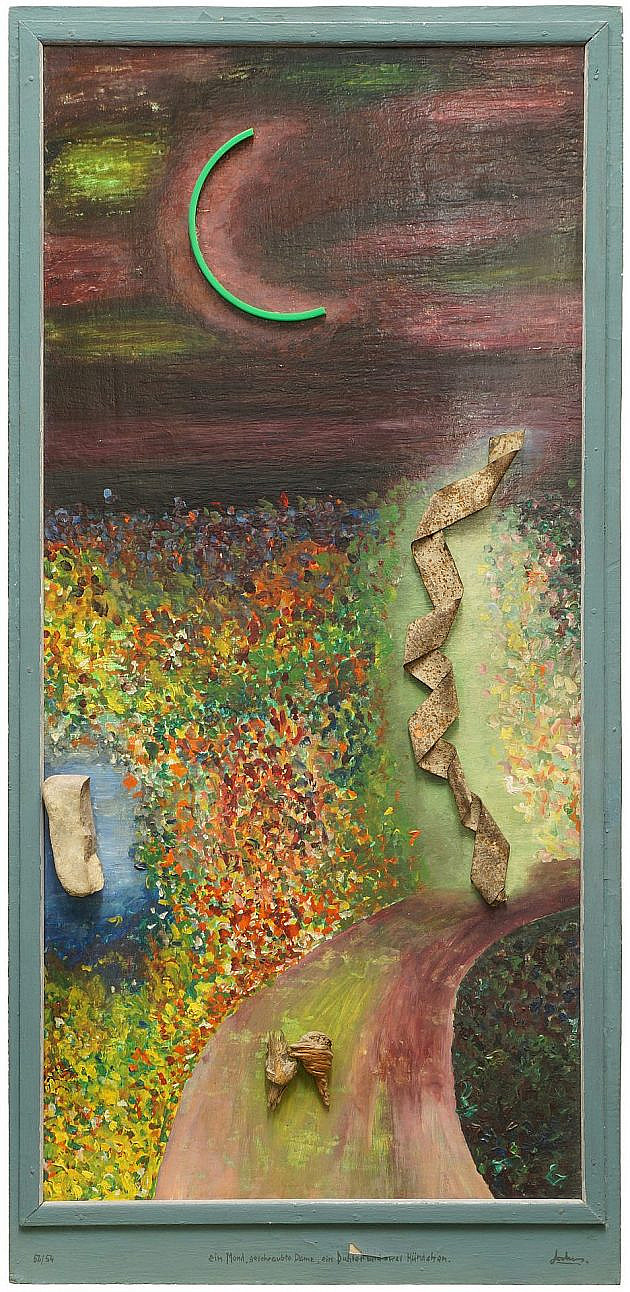

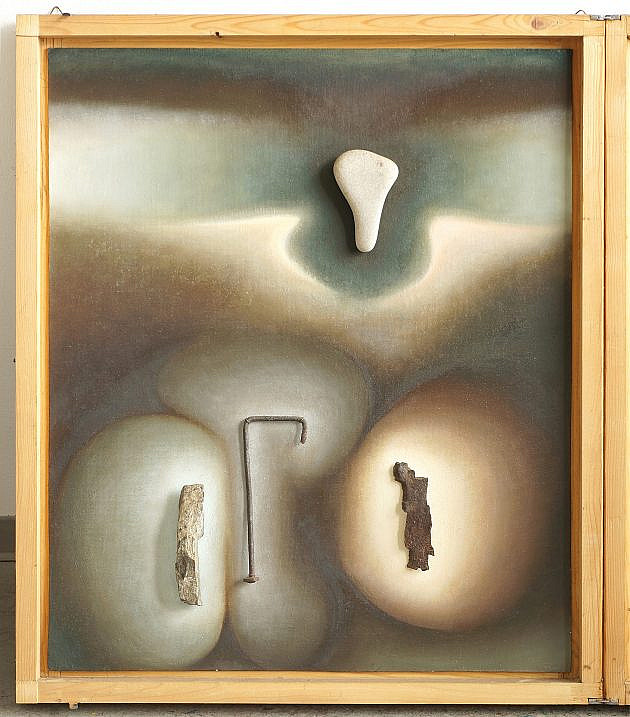

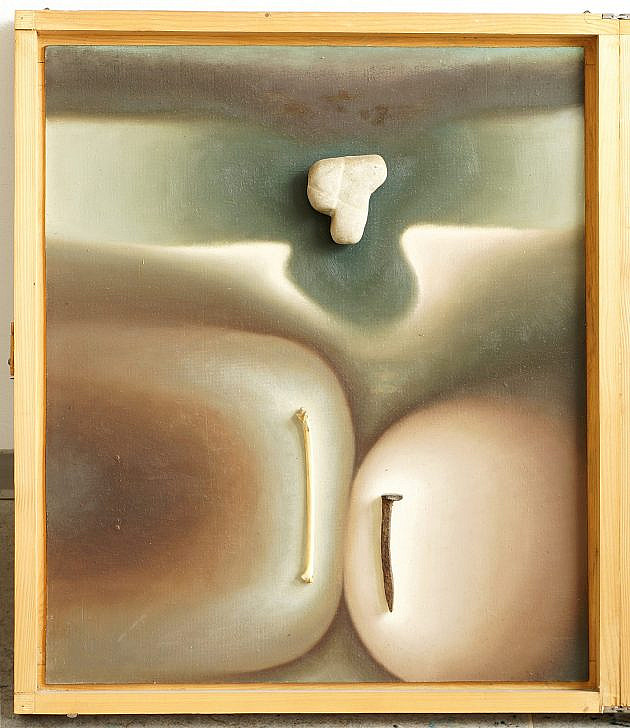

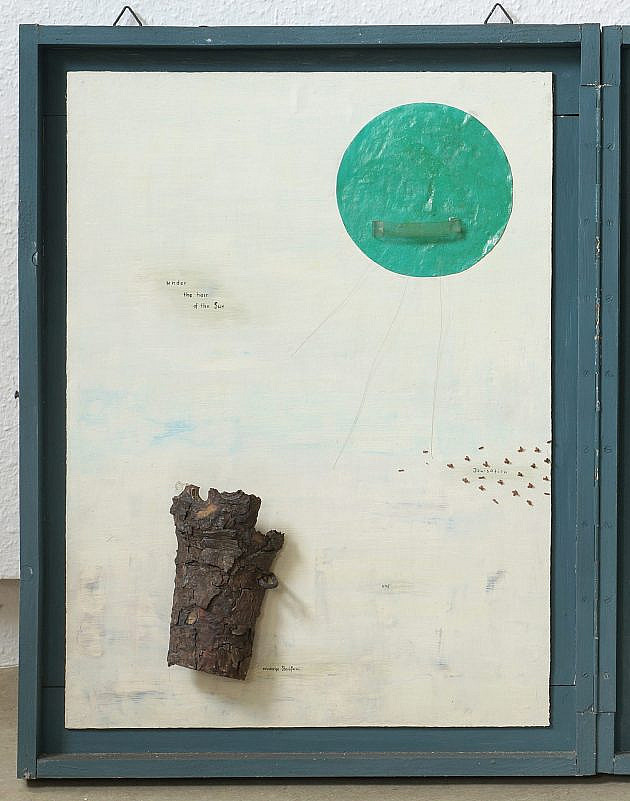

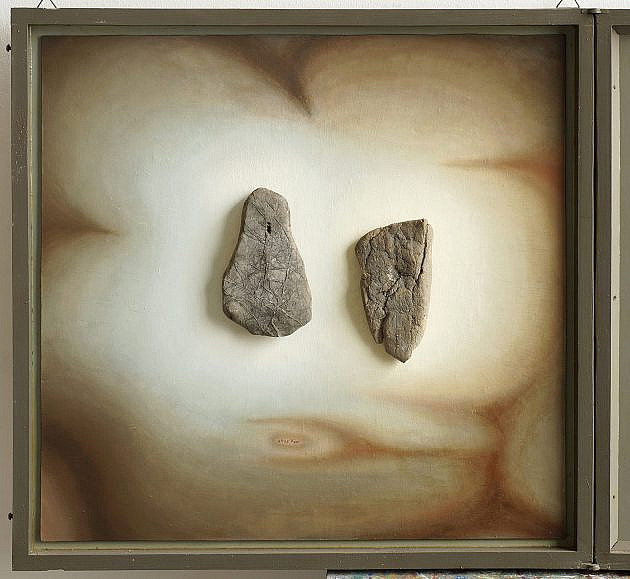

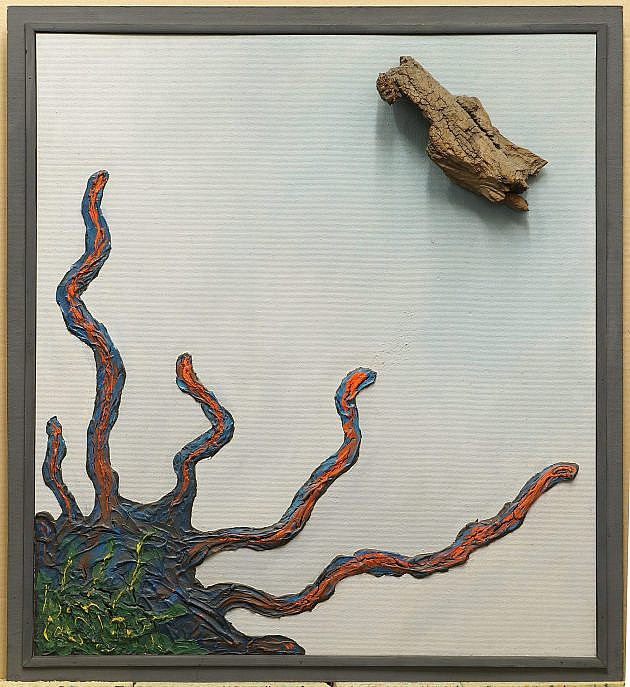

Jochims übernimmt oder variiert keine stilistischen Attitüden der Abstraktion, sondern vollzieht selbst den Prozess des Abstrahierens noch einmal in Auseinandersetzung mit dem Widerstand der Wirklichkeit. Erste Dokumente dafür sind die Bildkästen, die er seit 1955-56 herzustellen begann. Sie enthalten montierte Wirklichkeitsfragmente, Scherben, Steine, Fundstücke, die durch Anordnung auf der Fläche in ihrer Zeichenfunktion aktiviert werden. Zugleich treten sie in eine Flächenbeziehung, die sich dem Mittel der Farbe verdankt; sie erscheinen ummalt und damit auf die Ebene rückbezogen. Diesem primären Akt der Realitätsaneignung folgt ein Epilog, der sich auf dem Deckel abspielt, mit dem sich der Bildkasten schließen lässt. Seine künstlerische Behandlung setzt das Innere des Kastens um in die Dimension der Malerei. Das Innere und das Äußere treten in ein intensives Korrespondenzverhältnis, eröffnen einen metaphorischen Bezug. Sofern die Malerei des Deckels verdichtet, was unter ihm verborgen liegt, verwirklicht sich in ihr eine Art substraktiven Verfahrens. Dieser Vorgehensweise ist der Künstler auch in den späteren schwarzen Bildern in einer neuen Wendung gefolgt.

Die Bildkästen tragen alle Anzeichen einer Konzeptionssuche. Sie vereinigen in sich verschiedenen Elemente des Naturstudiums, der Abstraktion, der Bestimmung des Bildes als Ikone. Elemente, die Dank der Hilfe einer apparativen Anordnung zusammenkommen.

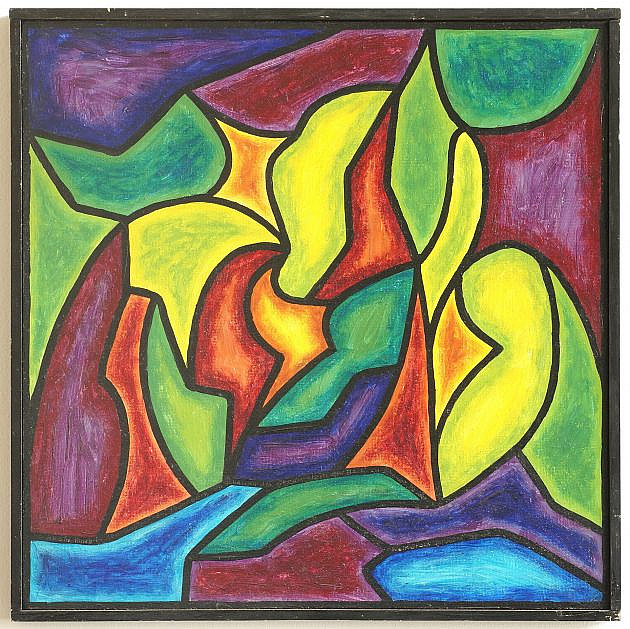

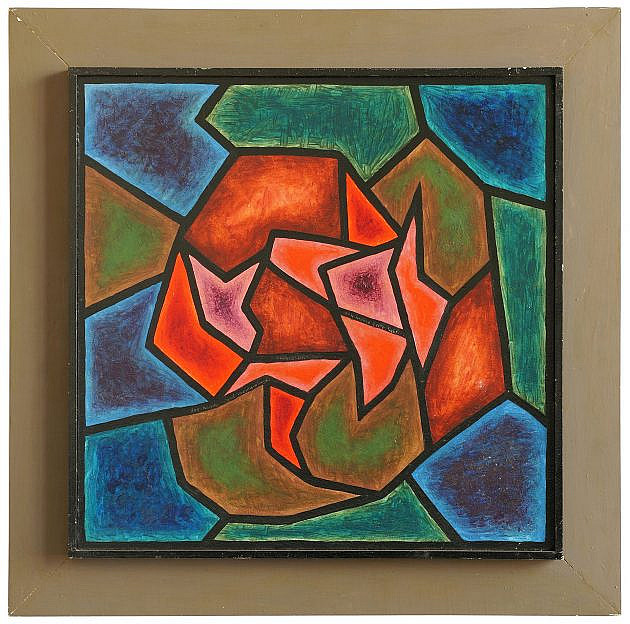

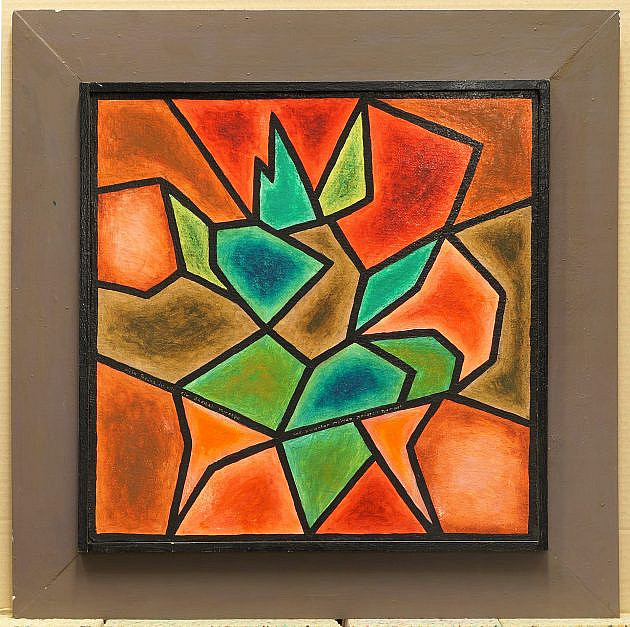

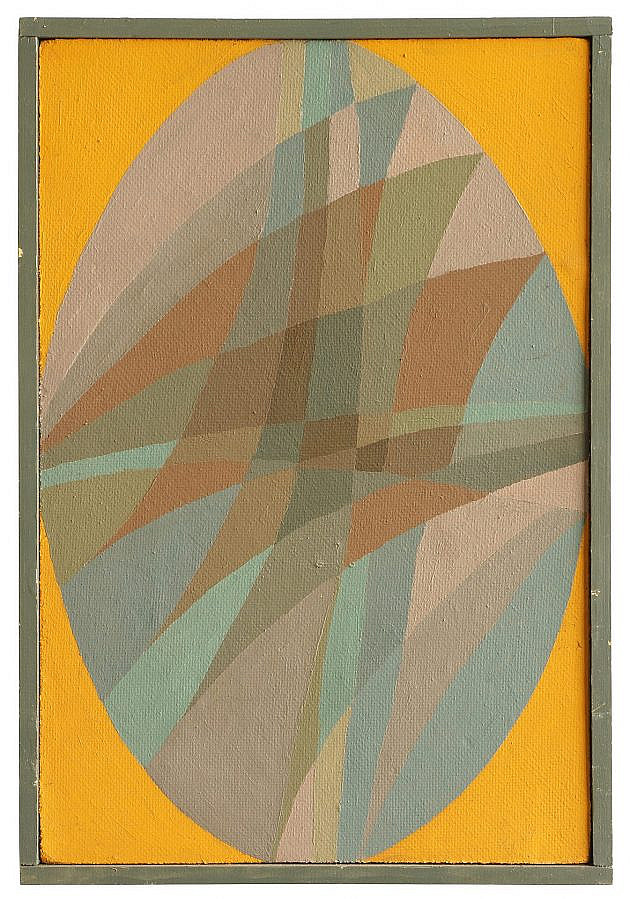

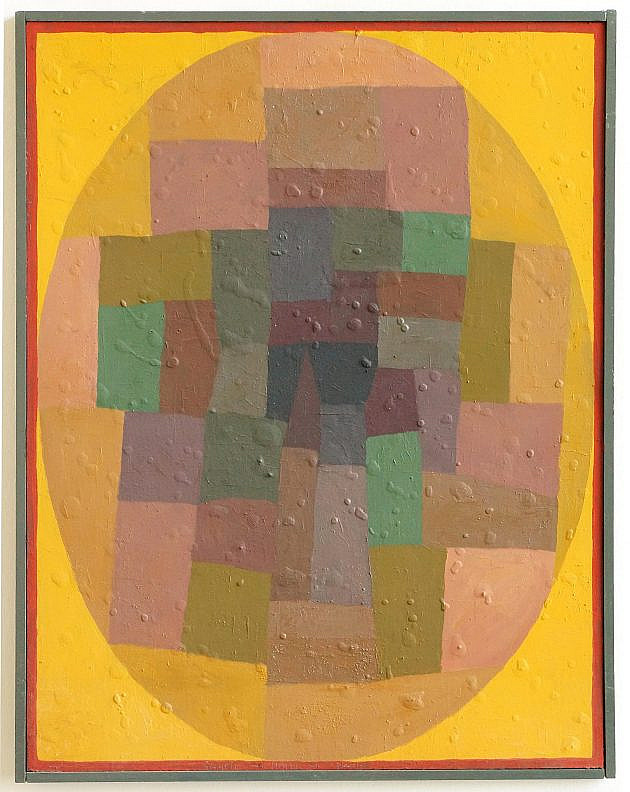

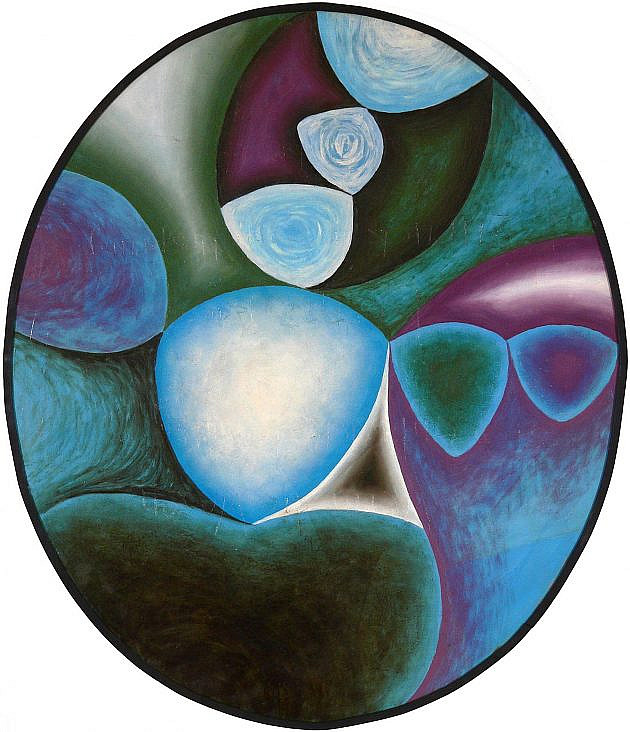

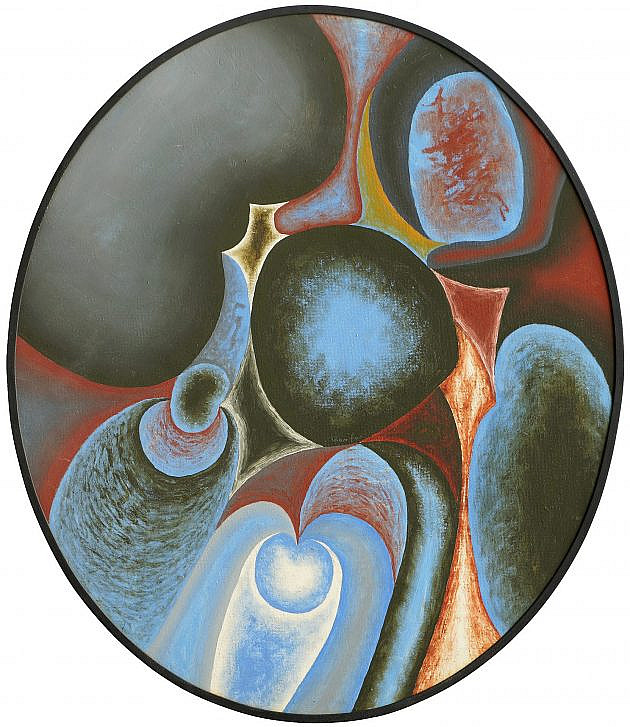

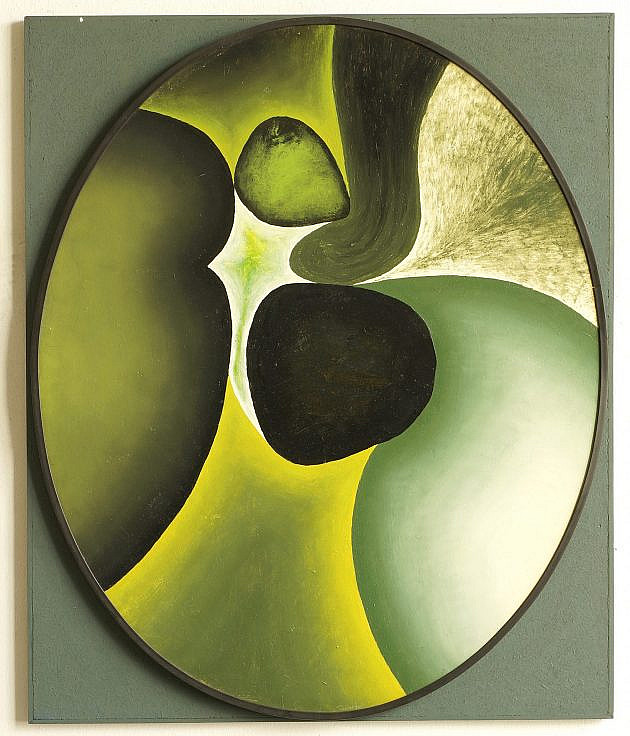

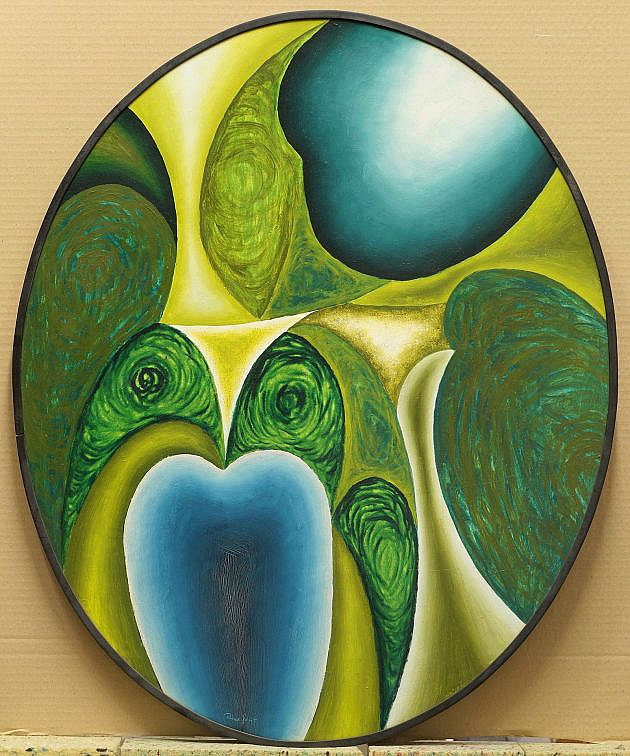

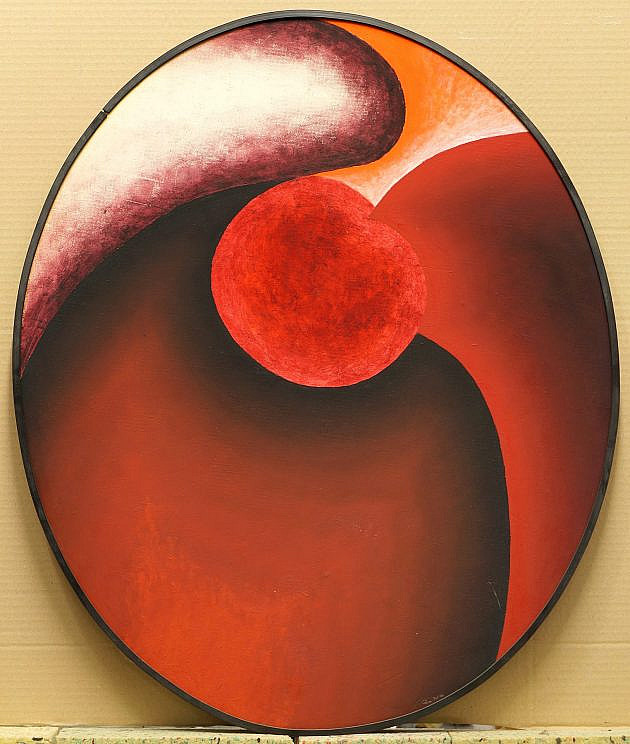

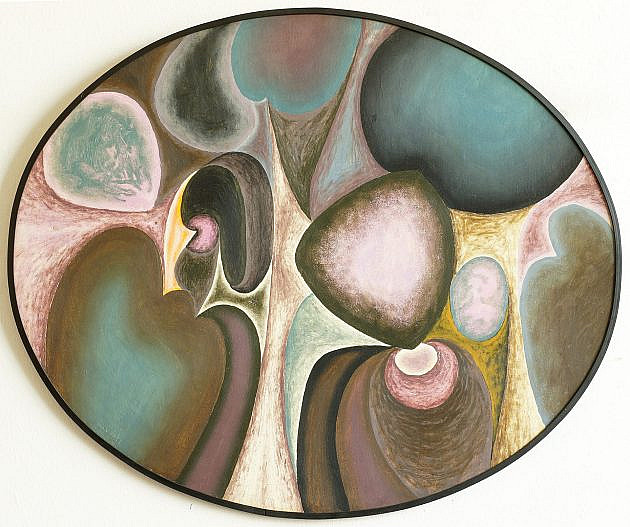

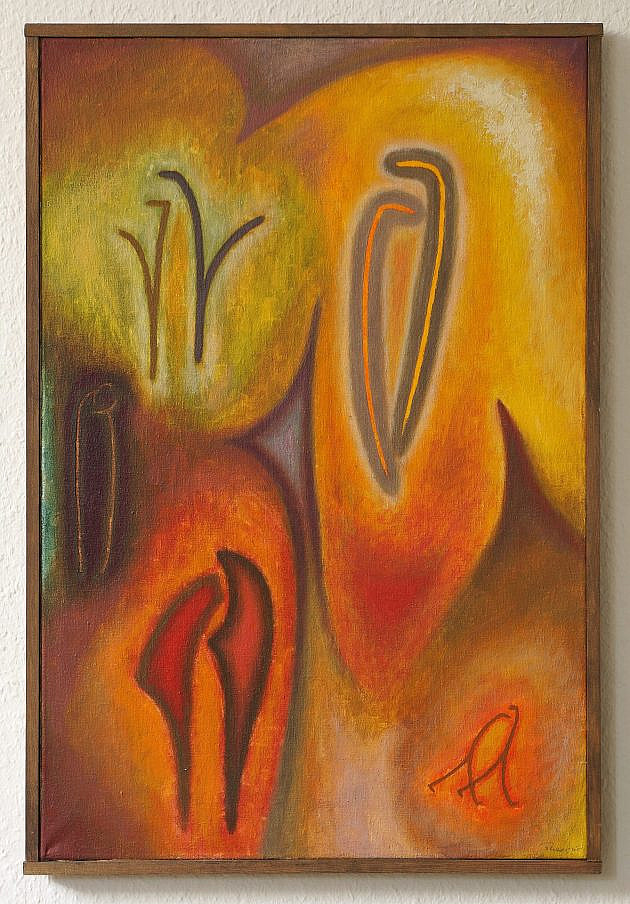

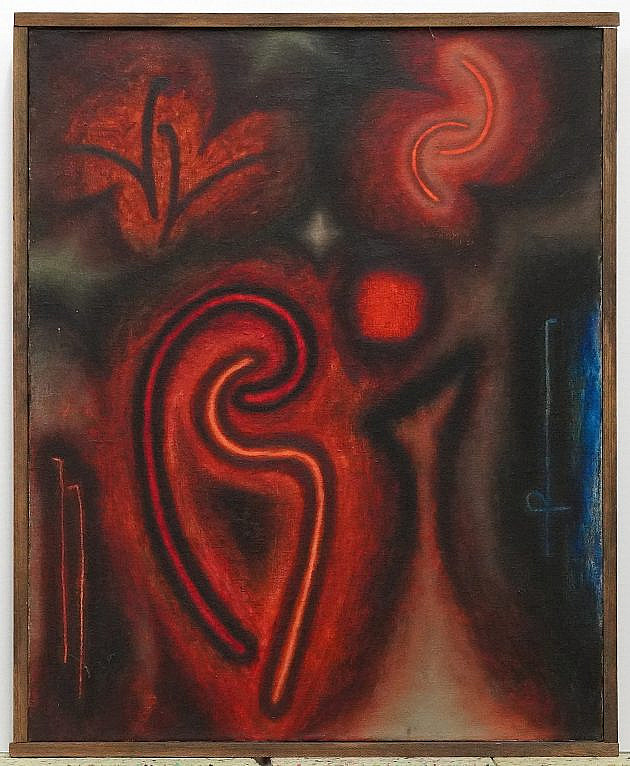

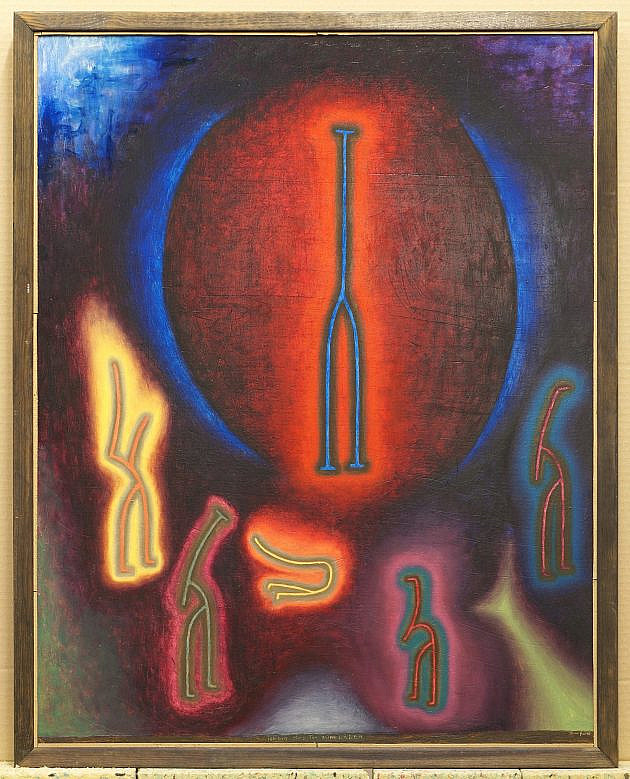

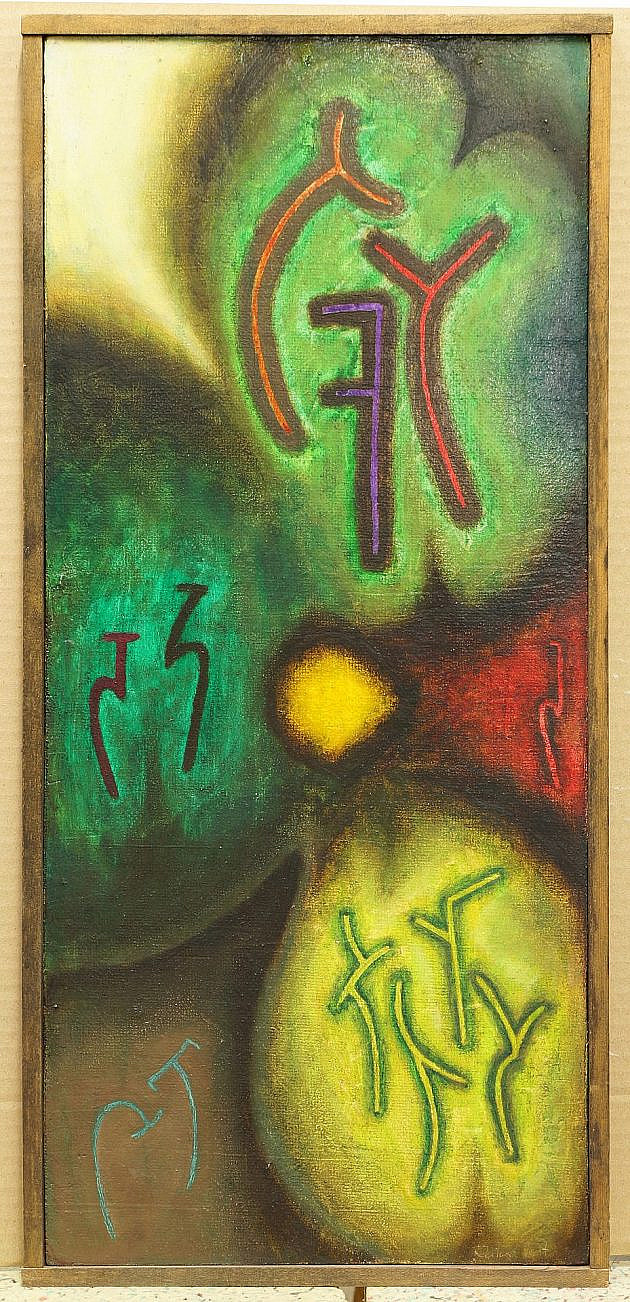

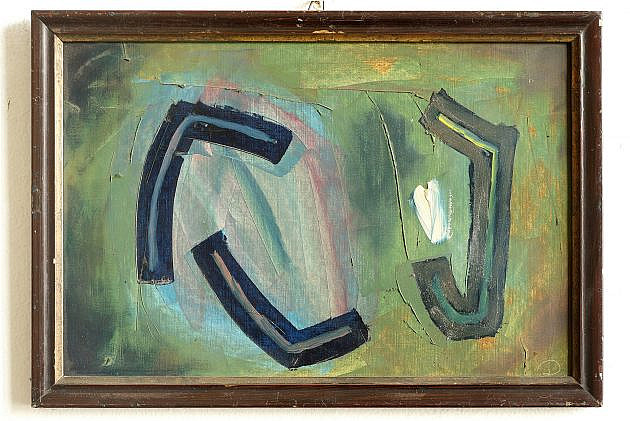

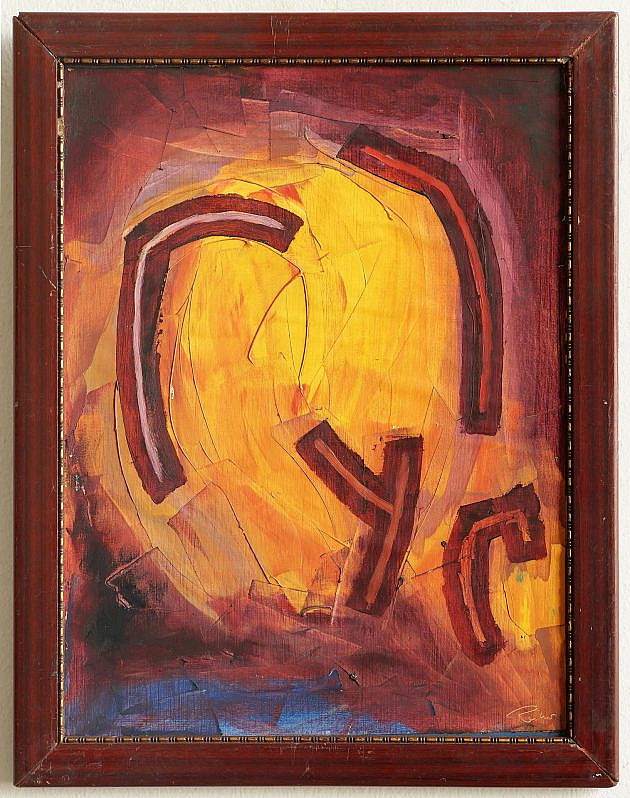

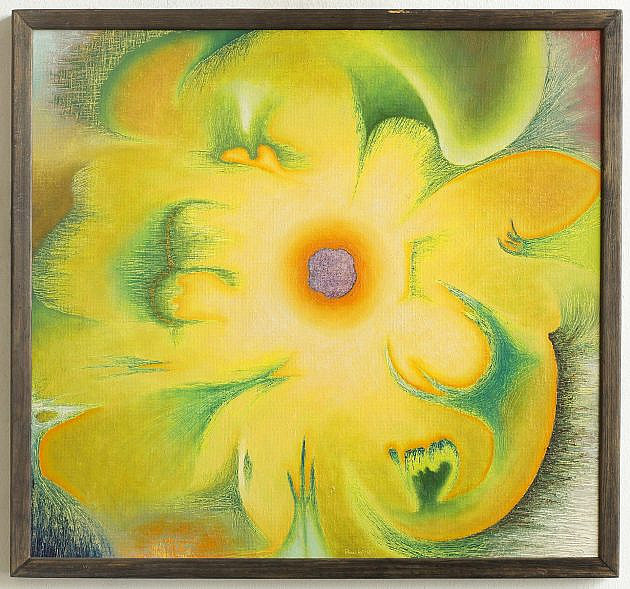

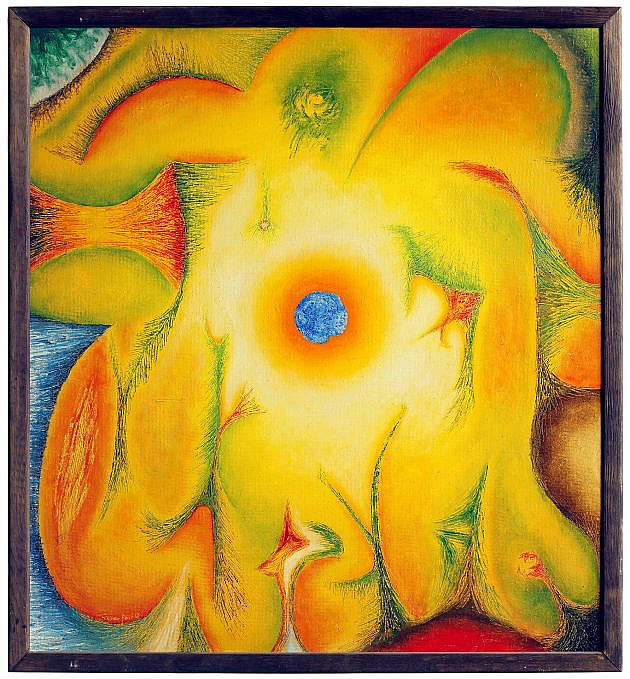

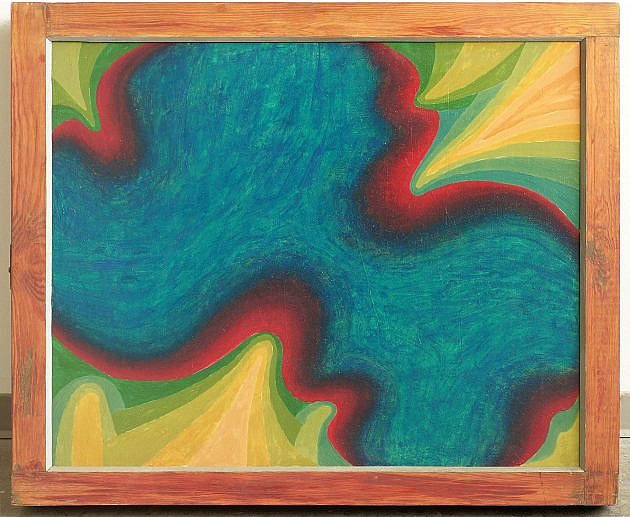

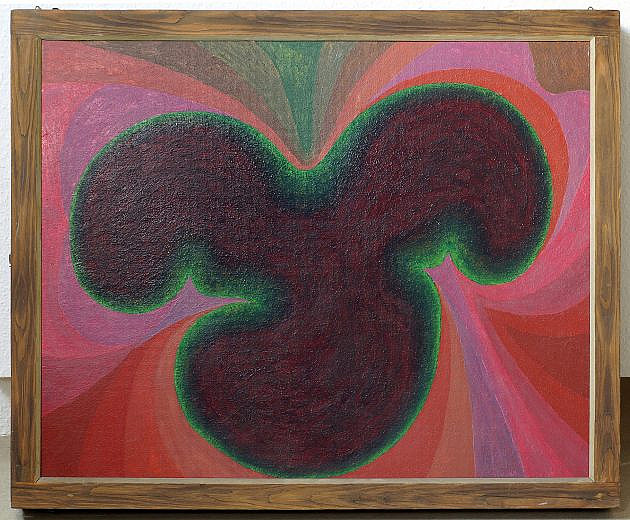

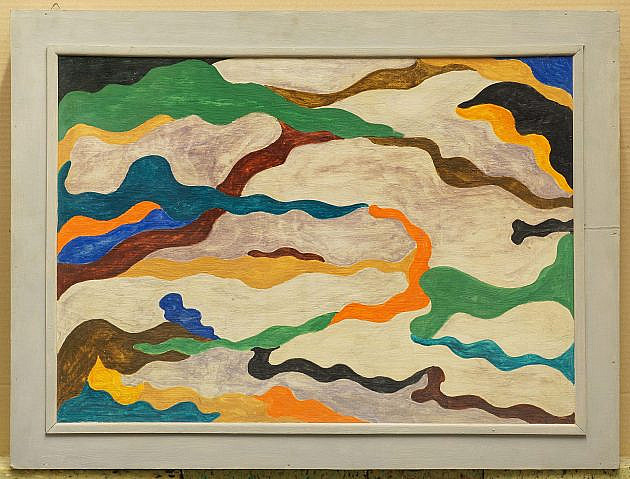

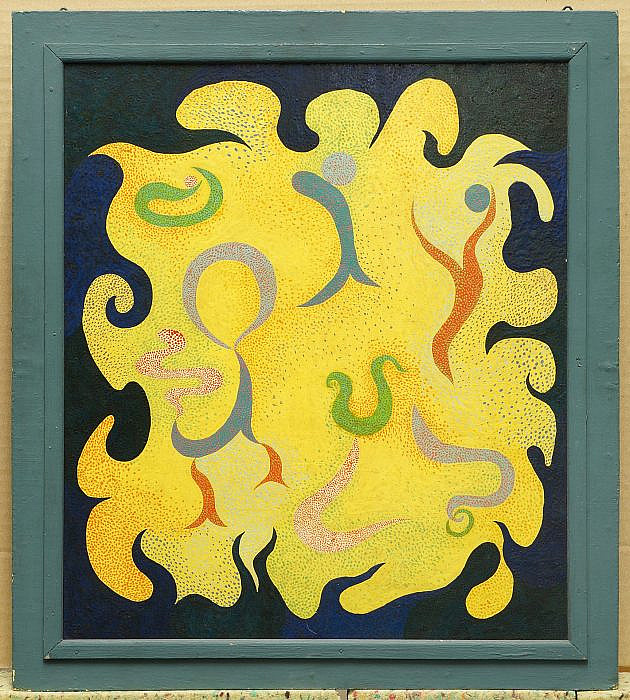

Mit den ovalen Bildern, die auf die Bildkästen folgen – Jochims nannte sie selbst Ikonen – ferner mit den kirchenfensterähnlichen Bildern intensiviert sich das Bedürfnis nach Konvergenz der auseinanderstrebenden Momente. Mit den C-Bildern schließlich erzielt Jochims eine tragfähige Formulierung dieser Fragen.

Bereits in diesen ersten Jahren lässt sich die Tendenz verfolgen, die Bildsemantik (erkennbar an der Zeichenfunktion des Gemalten oder der angeordneten Fundstücke) mit der Verschwiegenheit d und Verschlossenheit der Bildfläche zu vereinigen. Eine Tendenz, die in den Arbeiten seit 1973 die Gestalt einer planmäßigen Darlegung der Abhängigkeiten von Bildform und Bildfarbe angenommen hat. Die Doppelbilder und die einteiligen schwarzen, weißen oder grauen Bilder mit offenem Gestaltumriss knüpfen damit an Intentionen, die schon vor 1960 virulent waren.

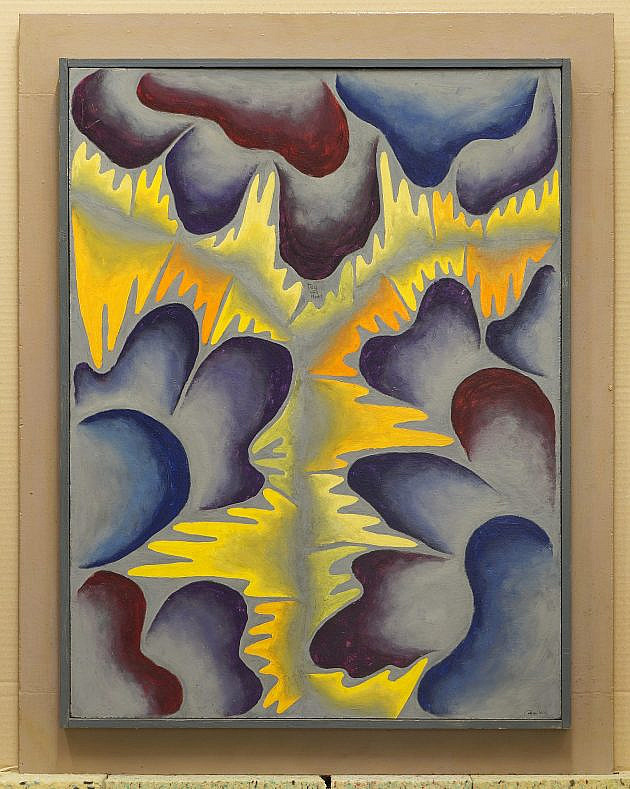

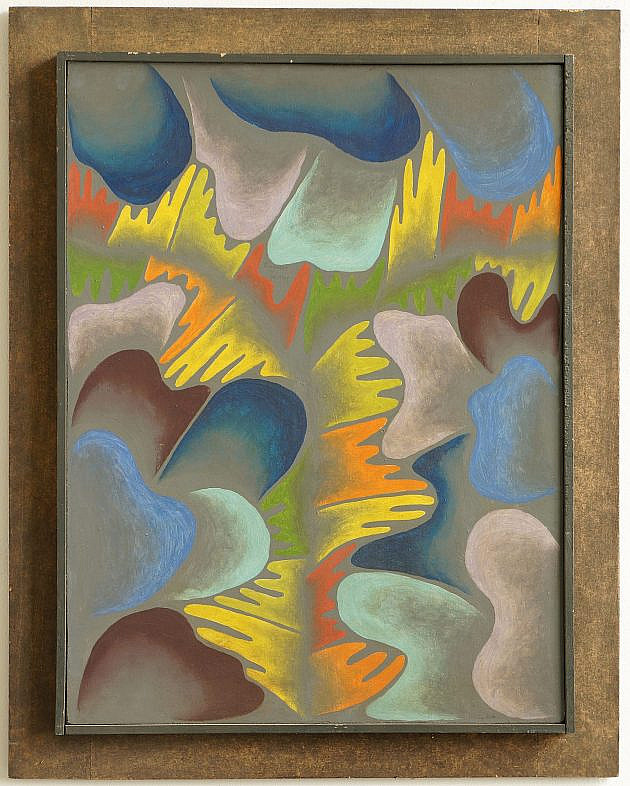

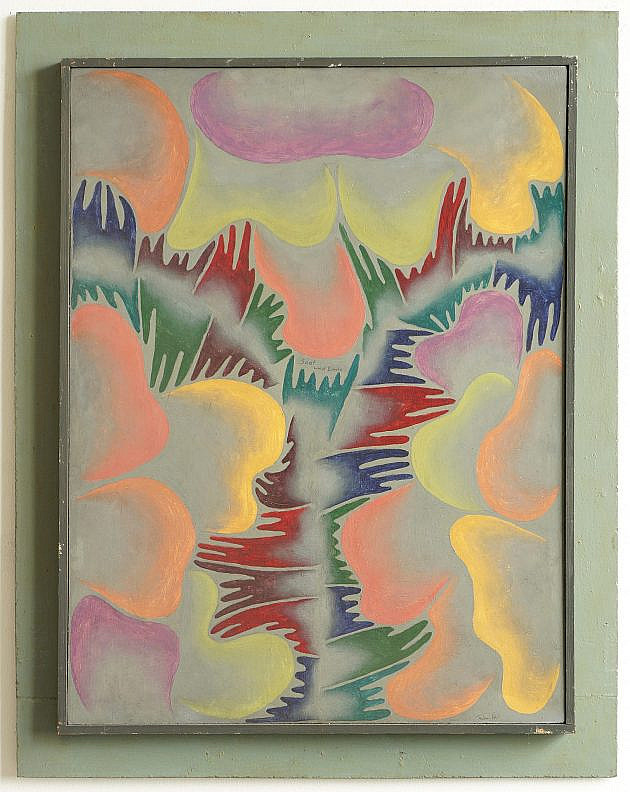

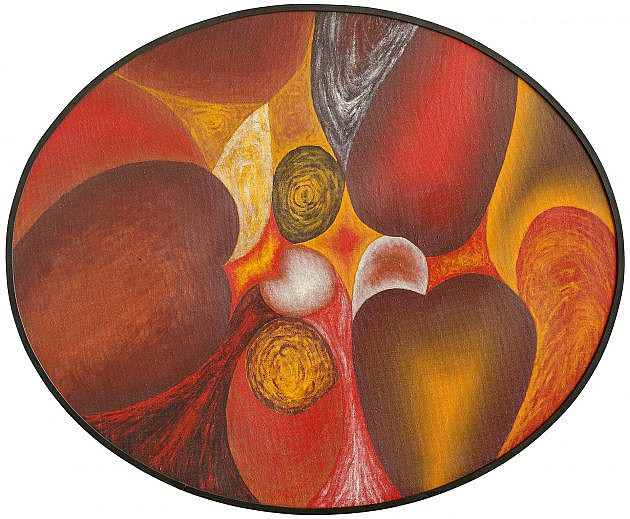

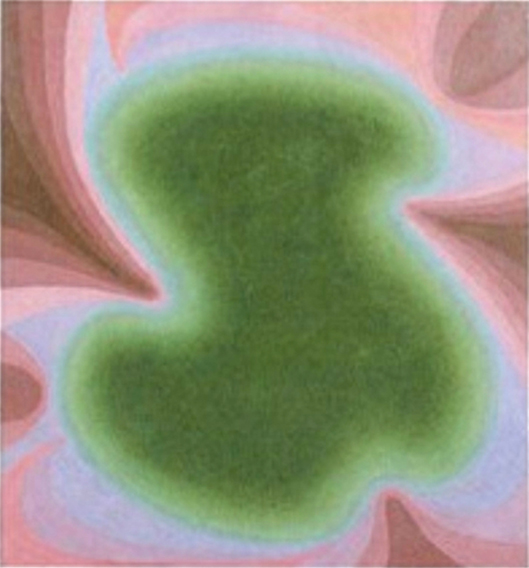

Mit den C-Bildern hat Jochims nicht nur das Auseinander von Innen und Außen, die Zeichenfunktion und das abstrakte Bildrechteck zusammengeführt. Er hat damit auch den Weg zu einer Lösung dieser Probleme mittels der Farbe gefunden. Denn die eingrenzende und doch offene Sichel der C-Gestalt lässt nicht nur Innen und Außen ineinanderfließen, drängen das Bedeutungshafte in das Bedeutungslose zurück , sie ist vielmehr auch im Zentrum des Bildes der sich öffnenden und schließende Schwerpunkt der Farbe. Die Bilder tendieren zu einer farblichen Einheitlichkeit, der man jedoch immer ansehen kann, dass sie Farbwidersprüche, das heißt konkurrierende Buntfarben, und gestische Spuren in sich zusammenbindet.Gottfried Boehm, Kunsthistoriker, Basel

The first pictures with which Reimer Jochims (at that time the artist still spelled himself with an “ei” instead of today’s “ai”, ed.) found his own artistic language bear the traces of a twofold exploration. They not only incorporate elements from post-war painting, but are equally characterized by an intense relationship to reality.

Jochims did not adopt or vary any stylistic attitudes of abstraction, but rather carried out the process of abstraction himself once again in confrontation with the resistance of reality. The first documents of this are the picture boxes that he began producing in 1955-56. They contain assembled fragments of reality, shards, stones, found objects, which are activated in their symbolic function by being arranged on the surface. At the same time, they enter into a surface relationship that owes itself to the medium of color; they appear painted over and thus refer back to the plane. This primary act of appropriating reality is followed by an epilogue that takes place on the lid with which the picture box can be closed. His artistic treatment transforms the interior of the box into the dimension of painting. The inside and the outside enter into an intense relationship of correspondence, opening up a metaphorical reference. Insofar as the painting of the lid condenses what lies hidden beneath it, it realizes a kind of subtractive process. The artist also followed this approach in a new twist in the later black paintings.The picture boxes bear all the signs of a search for a concept. They combine various elements of the study of nature, abstraction and the definition of the picture as an icon. Elements that come together thanks to the help of an apparatus-based arrangement.

With the oval pictures that follow the picture boxes – Jochims himself called them icons – and with the church window-like pictures, the need for convergence of the divergent moments is intensified. With the C-pictures, Jochims finally achieved a viable formulation of these questions.

Even in these early years, the tendency to unite the pictorial semantics (recognizable by the symbolic function of the painted or the arranged found objects) with the secrecy and closed nature of the picture surface can be traced. A tendency that has taken on the form of a planned presentation of the dependencies of pictorial form and color in the works since 1973. The double pictures and the one-piece black, white or gray pictures with an open outline thus tie in with intentions that were already virulent before 1960.

With the C-pictures, Jochims not only brought together the separation of inside and outside, the sign function and the abstract picture rectangle. He also found a way to solve these problems by means of color. For the delimiting yet open crescent of the C-shape not only allows inside and outside to flow into one another, pushing the meaningful back into the meaningless, it is also the opening and closing focus of the color in the center of the picture. The pictures tend towards a uniformity of color, which, however, can always be seen to combine color contradictions, i.e. competing chromatic colors, and gestural traces.

Gottfried Boehm, art historian, Basel